Return to Gompa Tong

The Self-Plagiarism of Erroll Collins

by Jim Mackenzie

It all began with “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia”, or so I used to think. I know better now.

I was watching “Indiana Jones and the Temple ofDoom” and it had reached that section where the hero was about to be thrown into a bottomless pit of fire. I was suddenly aware that I had seen it all before. No matter how grim the action became on screen, there was some memory inside my head of something that was far more terrible, a place of horror that I occasionally visited in one of my worst nightmares. Then, out of the blue, it came to me- “The Well of Fire” and the six-armed mechanical Buddha that had been programmed to cast its victims through a hideous mouth and down screaming into its depths. They were part of a tale that I had read in my childhood back in the 1950s – “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” by Erroll Collins. Somewhere in the house I still had a copy.

Shame overcomes me when I report to you that I rooted it out and looked at the inscription on the inside front page. It belonged to J. Mackenzie but the next page revealed the owner’s Christian name in full, John Mackenzie. It was my brother’s book. I had somehow acquired one of the icons of our childhood. When we played at cowboys with my other brother, the three of us had ready-made identities – like Billy the Kid, Jesse James and Wyatt Earp. “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” set us up with our names for the pirate air squadron that swooped over the bed clothes and round the back yard of our terraced house on Merseyside. Taking our turns at the different roles, we each played the part of the huge grizzly bear that was Zwort, the sly fox called Vornhorst and the enigmatic Scandinavian, Stockmar, the three flight-commanders of the Black Dwarf's’ pirate squadron.

Of course, we were also Barry Franklyn, Jimmy Vickers and Tommo Thompson, the lads from the R.A.F. who both outfought and outthought these wicked devils and eventually brought them crashing to justice.

Twenty years later my son was initiated into the thrills of “The Black Dwarf” when I used to read it aloud to him at bedtime. It was definitely more popular than “Biggles”. “Biggles” was okay but, by comparison, the villains had a pretty thin time of it. Zwort and Vornhorst have such a dramatic line in dialogue that part of the fun was cackling the lines at each other in the darkness after I had turned out the light.

All was well until at a jumble sale three years ago I stumbled onto a dirty brown book with the indistinct outline of a silver monoplane etched in the bottom right hand corner of the front boards. It was “The Hawk of Aurania” by Erroll Collins. Naturally, in spite of its dirt (and it is by far the drabbest looking book in my collection), I bought it and read it. Perhaps I could recapture the thrills of my childhood by a new Collins story. Foolish thought – this can rarely happen. Some of the ingredients were immediately familiar. It was a flying adventure with a dogged and resourceful British hero. There was a rebel squadron with black aeroplanes and distinctive markings and a suitably outrageous villain with a “Z” in his name. He was called Grotz and at one point he employed a henchman called Zwy. There was even a torture chamber scene with white hot branding irons available.

And now Larry noticed fantastic implements, sprouting from the heart of the embers. Pincers, callipers, branding-irons – all were there. Tongues of orange fire licked around them greedily, so that they glowed white-hot: molten pieces of metal, upon which the red sparks danced.

The story ended with a battle in the air between the “goodies” and the “baddies”. It was a reasonable read but it didn’t have the long-lasting effect of “The Black Dwarf”. However, with the advent of the Internet, I was able to establish that there were quite a few more Erroll Collins adventures out there, all with enticing and mysterious sounding names. I began to collect them but it has been slow going. This is one author where I may never reach the end of the trail. I also tried to find out a little about the author but nobody anywhere seemed to have heard of him. It was a bit of a mystery. It lingered at the back of my mind, waiting for a few more clues to turn up.

Then, all of a sudden, things started to happen. The “Collecting Books and Magazines” discussion group had from time to time considered authors who wrote about flying. I was proud, for instance, to have established once and for all that Percy F. Westerman and John F.C. Westerman were father and son. By the way, some reference books out there still have them as brothers! Kim Miles, inAustralia, ventured the opinion that the writing of Erroll Collins was somewhat similar to that of George E. Rochester. This didn’t sound at all likely to me until I thought about it for a while. There were certain similarities betweenRochester’s “The Despot of the World” and “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” but evil tyrants plotting from a far eastern base was probably quite commonplace. After all in "Biggles Hits the Trail” the most famous pilot of them all, had ventured to the Himalayas in search of the mountain of light and got caught up with the Chungs whose leader had pretty drastic plans for the West.

Nevertheless, in spite of my misgivings, I began to take a closer look at the work of the mysterious Erroll Collins. Simultaneously, the same team of enthusiasts who were classifying the storypapers and the annuals began to turn up stories by E.Collins and Erroll Collins in various publications of the 1940s and 1950s. I have in front of me, for example, the “Daily Mail Boys Annual” with a short story “Bandits and Bisnagas” by Erroll Collins between pages 23 and 29. In the same volume is “Dawn Patrol”, an “Air Police” story from Captain W.E. Johns.

At this point Steve Holland intervened in our discussions and produced the remarkable conclusion of his investigations which he will tell you about himself.

Back to the novels themselves. As I slowly built my collection to the small number of volumes I have today I began to notice certain common features, strands that would reappear no matter which book I had in front of me. As I put them together I began to understand just why “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” was such a special book in my childhood and why it is so satisfying to make the return to Gompa Tong that I mention in my title.

Let us take the heroes first. They are all English, of course.

In “The Hawk of Aurania” we have

the pleasant bronzed features of a lad in his late teens or early twenties…

and “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” gives us

a typical young Englishman, tall and athletically built, his well-cut features burned to a deep tan beneath somewhat unruly fair hair. His keen, grey eyes had a hint of laughter in them, though they met his senior’s scrutiny levelly enough

This is not surprising you may think. Indeed, both “Outlaw Squadron” and “The Secret of Rosmerstrand” contain heroes whose physical features are scarcely mentioned. Even the idea that these young pilots (they have always got to be pilots) are somewhat light-hearted or irreverent about their career in the R.A.F. or civil aviation is not uncommon in the flying stories of many authors. A part of the tone-setting is to have a section of the plot where they come up against something so dastardly that they are forced to become “deadly serious” for the first time. In Erroll Collins the requirements are very narrow: the hero must lose his best friend to an undeserved death (or supposed death) very early in the book. This then gives him a very personal motive for carrying on. Alongside a desire to save the world from a despot, a Ruritanian country from a tyrant orBritain from the Germans, there is nearly always the mission of revenge. Best of all is the moment when the hero gets a chance to settle his account with the villain by personal combat in the air. Thus Larry Maskell finally disposes of General Grotz over the aerodrome of the city ofVonda in Aurania.

Grotz, like a huge moth whose wings have been singed, dropped earthwards with the speed of a dart. His blazing parachute tore loose. A dreadful shriek of horror, which seemed to ring in Larry’s ears, burst from the doomed man’s throat. He saw the hard, level surface of the airport’s tarmac surging up to meet him.

Yes, thus end all villains. At this point you might suspect that Erroll Collins had been allocated all the awkward but high-scoring letters in a game of Scrabble in order to construct the villains’ names. Zwort, Vornhorst, Grotz, Zwy, Krog, Klosterberg, Wietzel (pronounced “weasel”), Tarak, Kraut, Zambro, Von Schornhorst, Grumm, all make deliciously sounding guttural noises when either rattled around the throat or spat out in anger. The “Black Dwarf” and “Black Sergius” hardly need any further build up to show they are not on the side of the righteous ones.

More surprising is to line up the names of the heroes. In “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” it is Barry Franklyn; in “The Star of Korania” it is Barry Grant; in “The Hawk of Aurania” it is Larry Maskell and, I see from one of my intact dustwappers, the following sentence advertising “The Sea Falcon” : “ Accused of espionage, BarryFalconer, the dare-devil air-ace escapes into the North Sea mists…..”. I know now it will be the first thing I look for when I acquire my next Erroll Collins volume. In “Outlaw Squadron” the hero is calledDerry Baxter and in “The Secret of Rosmerstrand” his name is Jerry Karslake. A surprising number of “Jimmy’s” figure amongst the best friends slaughtered (or maybe not !)

This playing with variants on the same “rr” consonants may strike you as bizarre but Erroll (notice the double rr) Collins is not unique amongst aeroplane authors in perpetrating this strange behaviour : John F.C. Westerman was fond of throwing in heroes who had the initials J.W. as a brief reminder of the three “John Wentley” stories will confirm. This is all harmless fun but it is a strange experience reading “The Secret of Rosmerstrand” which is all about war with the Germans and having to constantly remind yourself that “Jerry” is in fact the hero. But really the game is given away in this same book when I learned that the scientist employed in developing the weapons of destruction that will wipe outBritain was called Kramzin.

“Hang on,” I thought, “I’ve seen this somewhere before.”

Indeed I had, it was in “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia”. Hurriedly I checked it out. No, he was called “Khamzin” and it was poison gas that he invented. Kramzin (notice the subtle difference) , the brilliant but deviant inventor in “The Secret of Rosmerstrand” had developed the aquatank. This was an enormous submarine or U-boat that had the additional capability of marching on land or over the sea-bed because it was also fitted with caterpillar tracks. The invasion plan was to creep across theNorth Sea and up the main rivers well intoBritain, launching a joint attack with thousands of parachutists after the R.A.F. had been wiped out. Don’t worry it didn’t succeed, for, thanks to the hero, the Royal Navy were warned.

For hours ships and planes cruised over the same spot, hurling depth charges and whistling torpedoes into the sea at such a rate that the water was churned and pitted into surging foam, while the thunderous roar of countless explosions rocked houses on the distant mainland and vibrated the windows of every parish.

In idle moments I sometimes wonder what the effect of a story like this would be in the middle of war-time. To a boy receiving “The Secret of Rosmerstrand” as a present, and my copy has the following inscription, “Wishing you a very Happy Xmas for 1942 – love Dad” written on the front paste-down, did it help for him to know that the Germans were so efficient that they could build super-submarines that could turn into tanks ? Did he worry that mad European scientists were developing gas bombs that could reduceLondon to craven surrender ? Yes, although Kramzin (or was it Khamzim ?) didn’t invent the gas in “The Secret of Rosmerstrand, I find just such a gas bomb factory in “Outlaw Squadron”, where the evil Krog, like the good Nazi that he is, tests out the effectiveness of the poison on an innocent swan.

Only a heap of feathers, scorched brown as if by fire or some powerful acid, remained to tell the fate of the victim.

By the time we get to “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” the eponymous villain is conducting his test bombing on nearby Mongolian villages who all live in fear of the gas called “The Creeping Death”.

You could see that it had begun to dawn on me that most of the ingredients that I remembered so well from “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” had been tried out earlier in the war-time novels that had preceded it. Erroll Collins was recycling old plots, old characters and even old names. This was self-plagiarism on a large scale.

You are still not convinced, perhaps. Let’s branch off into a different direction for a while. I haven’t quite told you everything. You see, when listing the heroes in one of the earlier paragraphs I deliberately kept from you the fact that “The Star of Korania” is in fact a girl’s book and that Barry Grant, although qualified by the nature of his name to be the leading character, is no more than a second or third fiddle to the characters who dominate the action of the book and these are the heroines – Jane, Pat and Zita. Aha ! You say “Zita” – a “z” in the name is a sure sign that she is one of the baddies. Not so. You see Zita is not her real name. Her real name isXenia and she is the princess of Korania and she is the rightful heir to the throne of this strange Balkan country. Admittedly “Xenia” is not quite the name you would choose in Erroll Collins country if you want to play the heroine – it still contains a letter from suspiciously near the end of the alphabet.

But by now you will have realised that with Erroll Collins that all is never as it seems. Even that list of villains – “Zwort, Vornhorst, Grotz, Zwy, Krog, Klosterberg, Wietzel (pronounced “weasel”), Tarak, Kraut, Zambro, Von Schornhorst, Grumm,” I quoted to you earlier contains one that is working for the forces of good under a very necessary alias. Take your pick.

With Jane and Pat andXenia there is still plenty of pluck to be shown and this demonstrates that the girls are either true English or, if foreign, worthy of being monarch of a troubled state. There isn’t quite as much pugnacity and I can’t remember any villains whose faces are reduced to purple bruises or whose yellowed teeth are smashed down their throats but, make no mistake about it, these girls are pretty determined and can take care of themselves. Jane for instance, who has only just gained her ‘A’ licence, is able to hold her own in a dogfight.

Only Jane’s skilful stunting preserved the girls from destruction. The loops, rolls, and zooms into which she flung the long-suffering machine afterwards made her shudder. Certainly, her tactics made accurate shooting very difficult for the enemy.

Naturally it must help to have the future Queen of Korania as one of your tail-gunners.

Earlier in the book, however, I came across a passage where Jane is perilously inside a basket attached to a rope leading to the top of a high crag where a mule is used as the power for a capstan that winds the human load to the inaccessible plateau. On the high plateau is the brigand’s stronghold. Now this is exactly the same way that Jimmy Vickers gets up to the high plateau and approaches the odious monastery of Gompa Tong in “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” even down to the oisers and the wickerwork of the basket. There’s another good idea that the author decided to use more than once. Erroll Collins must have felt pretty safe – after all what boy would read “The Star of Korania” where on the first page there is an extensive description of young Jane with her “violet-coloured eyes” and “the black curls escaping from beneath her natty white cap” ?

But I doubt if the author ever bothered to worry about such details. Certainly there were no qualms about using the cowardly Italian pilot character more than once. In “The Hawk of Aurania” it is Salvini who attempts to down our hero, whilst in “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” the braggart di Vulpi is despatched to no one’s regret. It’s a pity that Salvini forgot he was Italian and cried out “Caramba” in Spanish as his opponent’s tactics began to tell on him in his final aerial duel. Still he got what he deserved for being foreign and for belonging to the black squadron instead of the blue. Khamzin’s outcry against the British in “Black Dwarf” is phrased in almost identical words to Kramzin’s in “The Secret of Rosmerstrand”. Further examples multiply from the constant use of gipsy brigands, fog in theNorth Sea, underground rivers, parachute descents (There’s one in every book I possess by Erroll Collins) to the details of actual words. When wounded in his cockpit or partly drugged by poison gas, the hero pilot (male or female) is sure to feel the wind in their faces “like a cold douche” to bring them round for one last despairing effort.

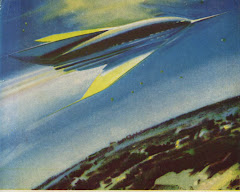

Most remarkably of all, even when Erroll Collins launches into science fiction with “Mariners of Space”, the same features start occurring. I must admit that I started this book with some trepidation. After all I had some experience of perfectly respectable flying adventure authors who make fools of themselves when they attempt another genre. W.E. Johns’ space series is not a patch on Biggles, Worrals or Gimlet. I prefer T.C. Bridges’ characters deep in the Amazonian jungle rather than grappling with death stars. Initially I was lulled into a false sense of security – the hero of “Mariners of Space” answers to the name of Colin Devenish – not a double consonant in sight. On the other hand one of the Martian officers was called Xantra and this put me on my guard. Pretty soon the familiar pattern began to emerge.

This time the hero belonged to the Space Rangers, wearing a silver comet on his lapel instead of the traditional wings. He too was surrounded by fellow officers (one of whom, inevitably, is called “Jimmy”) by whom he was shown a tremendous amount of loyalty.

The villain in the flying stories had a pretty clear-cut job: he would either be helping Hitler take overEurope, be a petty tyrant wanting to throw out the rightful heir to some Ruritanian Balkan country or a madman bent on world domination like the Black Dwarf. The villain in “Mariners in Space” was plotting the subjugation of the universe to Martian rule. Of course a few Martians are decent chaps and throw in with the hero to help thwart the dastardly plot of their fellow planet-sharer.

“Mariners in Space” abounds with advanced technological gadgetry, yet, you will relieved to know, there is still a place for the good, old-fashioned parachute. Not so pleasant is the thought of visiting the officers’ dining arrangements.

Space-Captain Jan Marthus of the Martian Space Fleet steered his friend into the restaurant.

“How about a steak ? he invited, as they approached the glass cabinet, where red meat cells, fed by a culture, multiplied before prospective diners’ eyes.

In an underground cave system beneath the red soil of Mars, a group of people called the Taans keep the tradition of the “good” brigands alive and well.

Colin had heard of this mysterious Martian tribe. A race akin to the Aztecs of ancient Mexico, they dwelt in the Red Planet’s deserts, guarding their rites and customs jealously.

Pretty soon the Taans lead them to another new yet somehow familiar sight,

The noise increased, but mingled with its thunder were the hiss and crackle of flames. A lurid, crimson glow wavered at the end of the tunnel. Then suddenly the passage widened out into an enormous cave.

The Earthmen recoiled from the branding heat, clapping their hands before their eyes. Out of a broad vent, set high up in the most distant face of the cave, poured a veritable river of flame. It swept in a crimson cascade over a series of ledges, to hurl itself with a sudden roar into a whirlpool of molten rock which eddied far below. Clearly this pool was the crater of some subterranean volcano. Spanning the fiery pit was a natural arch of rock.

We’re back to the “Well of Fire” that began this article. Some things never change, especially the deference shown by other ranks to the officer class. In this sparkling technological world of the future where space-ships are as commonplace as aeroplanes, the mechanics still refer to their friends, whose lives they save, as “Mr. Colin” and “Mr. Jimmy”. This continuity of class difference, implicit in the author’s style of writing, is both alarming and reassuring. To be honest, however, I have to admit that I liked “Mariners of Space”, though perhaps for the wrong reasons. Particularly rewarding to me was the way in which Erroll Collins tried to take conventional dialogue and give it a “futuristic” tang. In the “real” world of Korania,Aurania, Mongolia or Rosmerstrand, the rogues always contemptuously referred to the young British pilots as “cubs” and the heroes responded by using the expressions “scuts” or “swine”. In Space it is different. Martian pride and superiority are now conveyed by epithets like “contemptible Earthling” or imprecations like “Go to Jupiter !” Most amusing of all, however, are the expressions used by Colin and Jimmy when angry with themselves or frustrated with each other.

“I could kick a comet !” says one.

“Don’t be an asteroid !” replies the other.

Then there’s Debra Marka.

Who ?

What ? Perhaps some gorgeous girl from Venus who gets their hearts in a twist ?

No such luck. It’s the name of the capital of Mars.

At the end of “Mariners of Space” there is, as usual, a glorious final bust-up between the forces of good and evil. This time space-ships, not aeroplanes, are the combatants but there is still room for clever manoeuvring and the rites of single combat. Action sequences like this are Erroll Collins’ speciality. There is still a universe to be rebuilt at the end.

What of “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” after all this cynical research into the author’s other books ? It was time for a re-read and perhaps a re-assessment. Could it still survive my knowledge of all the bits and pieces from earlier works which had been thrown in and re-cooked ?

The answer is an unequivocal “Yes”. If you have to read just one Erroll Collins book in your life-time, then this is the one. All the books have pace; all the books have “interesting” characters and enough twists and turns in the plot to keep you guessing as to what is about to come next. But I think that the “Black Dwarf” has several extra ingredients that set it apart from the rest of this writer’s work. First and foremost amongst these is the surprising female component. Although Jane and Barry in “The Star of Korania” have the kind of joking relationship that is based on good companionship and mutual admiration, it is never allowed to turn into anything more substantial. We are always reminded that they are cousins. Surprisingly even Princess Xenia with her “glorious reddish-gold hair”, and her “creamy-skinned oval face, strengthened by a determined chin, and striking, amber-coloured eyes” does not seem to destined to find a consort. In “The Black Dwarf of Mongolia” we have Marie who becomes a very important part of the story and an important clue to the psychology of several of the characters. She affects the hero, Barry Franklyn, to such an extent that he proves vulnerable to her charms and her strength of character. Where Biggles, for a while, has Marie Janis, “a vision of blonde loveliness”, Barry becomes captivated by Marie Khamzim:

The girl was beautiful. Her waving, golden hair set off a charming, oval face, with a complexion of roses and cream. A face strengthened, however, by a firm, though smiling red mouth, and a dainty, but resolute chin.

How can such a splendid girl be the daughter of Khamzim, the scientist who has produced the poison gas that will surely wipe out the world upon the instructions of the malevolent dwarf ? The local natives, entranced by her appearance and her captivating manner, have declared that she is a special White Goddess, like the one in Tibetan legend. These mysteries bolster the usual story-line about outwitting a tyrant and his affection for the girl gives Barry another very personal motive for defeating his enemy. It also, as you might expect, makes him extra vulnerable when her life is danger. Another female character, Lalla, Marie’s ancient Chinese nurse, provides yet another dimension to this story. She is torn by her allegiance to her master, Khamzim, and her devotion to young Marie. She is also the bearer of a great secret that is only revealed at the end.

Indeed some of the minor characters in this book are drawn very well indeed. The three flight-commanders of the Black Dwarf’s pirate squadron are individualised in quite a surprising fashion. Zwort and Vornhorst are the usual “scum of the earth” but the Nordic-looking Stockmar is a puzzle. He has joined the pirate squadron for adventure and still entertains romantic chivalrous notions about a fair fight. So un black-and-white is his character that the reader becomes concerned about his fate as the book moves to its climax.

Lo Minh, the son of a local tribal leader, proves an interesting subsidiary hero who plays his full part in the overthrow of the sinister Gompa Tong regime. To him, indeed, falls the honour of the by-now “traditional” parachute descent. Blind faith in his friend Jimmy allows him to catapult himself bravely into space from the mountainside in order to rejoin his people and lead the attack on the gloomy monastery. Lalla’s escape from the prison cell is done by a trick which I have never seen repeated anywhere in children’s or adult fiction.

The malevolence of the central villain, the Black Dwarf, is created not just by his confrontation with the British heroes but by the way he deals with his own underlings. The scene where he promises a reward to a faithful native who helps him to hide the gold bullion treasure is a classic of horror.

“For your services tonight I must reward you. Kneel down on yonder ledge, and gaze into the water. There are other treasures in the Dragon Lake, and one of them is for you !”

Kasim obeys and the Dwarf stabs him in the back.

“I have kept my word, Kasim !” he whispered. “There are other treasures in the lake – and one of them is sleep. Sleep well.”

In fact, when I look at the dialogue of the book more closely, I realise that I was wrong. It is not the duel of words between Zwort and Vornhorst that drips the most crisply from my lips but the Black Dwarf’s cackling reflections as he gloats insanely over his malignant plans for success. How satisfying then what happens to him and Zwort in the end. But I must not anticipate your reading.

I shall go on collecting the work of Erroll Collins, even the short stories in annuals, but I suspect that as I do so, I already realise that none of them will ever recapture the magic I felt when I first read this tale and played those silly games with my brother, John Mackenzie, to whom I dedicate this short article.

Now I am off for a “cold douche” after all this remembered excitement.

Tuesday, 7 April 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)